Spring/Summer 2022, Issue 6, pp. 12-17

[Online 6 Jun. 2022, Article A032]

[PDF]

How Religion Motivated Smallpox Eradication

Doug Oman[1]

-

-

The PHRS Bulletin publishes a wide range of articles, with purposes ranging from education and pedagogy to advocacy to theoretical or historical reflection. In this piece, Doug Oman discusses roles of religion highlighted in two recent memoirs of smallpox eradication leaders, arguing that the public health field needs histories that better address and integrate the role of religious and spiritual factors.

-

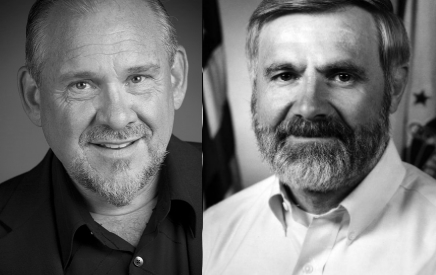

How many of us in public health know that religion performed diverse and perhaps crucial functions in motivating global smallpox eradication, often hailed the greatest public health triumph in history? Religion’s roles in smallpox eradication are seldom recounted in public health teaching and discourse, perhaps because previous histories have emphasized technical and managerial strategies, ignoring religion or framing it as an obstacle. But such truncated views of history do not optimally prepare us for a global, multicultural future in which religion remains a powerful force. Happily, as described below, a much wider range of religion’s roles in global smallpox eradication – sometimes astonishing – can be gleaned from two complementary and recently published memoirs by smallpox eradication leaders William Foege (2011), later director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and Larry Brilliant (2016), later the founding director of Google’s philanthropic arm, Google.org.

It should not cause surprise that religion played important motivational roles in the historic smallpox eradication campaign of the 1960s and 1970s, as religion is among the most powerful human motivators– perhaps most commonly in ways that support health and well-being (Oman & Syme, 2018). Healthy lifestyles, for example, can be motivated by concern for stewarding one’s body as a sacred “temple.” Such shared concern for bodily health undergirds the widespread collective partnering between public health professionals and religious communities (e.g., Idler et al., 2019; Kegler et al., 2007; Whyle & Olivier, 2017). And religion is often a key influence on discernment of personal “calling” (Dik et al., 2009; Oman, 2018). But as described in these memoirs, especially by Brilliant (2016), religion’s motivational functions in smallpox eradication extended far beyond conventional categories.

Global smallpox eradication is one of humankind’s greatest triumphs: Smallpox had killed, often horrifically, approximately one third of a billion people in the 20th century alone (Henderson, 2011, p. D8) – a number that dwarfs the recent toll from COVID-19, and even dwarfs the 1918 influenza pandemic. Spread by respiration and face-to-face contact, the inhaled smallpox variola virus invaded the body’s respiratory tract, proceeding to lymph nodes, bone marrow, and bloodstream, and commonly producing pustules covering large areas of skin, fever, nausea, bleeding, and death for about one-third of victims. “Textbook descriptions miss the often catatonic appearance of patients attempting to avoid movement, the smell [and] isolation imposed by the disease…. Although many diseases and conditions are tragic, smallpox was in a class by itself for the misery it inflicted on both individuals and society” (Foege, 2011, pp. 22-23). Smallpox was “by far, the most persistent and serious of all the pestilential diseases known to history… more feared than any of the [other] great pestilences – more than plague or yellow fever or cholera or malaria… there was no treatment” (Henderson, 2011, p. D7).

But in the late 1960s, there was no overabundance of motivation for pursuing the patient, persistent work of eradication, perhaps because so many people viewed full eradication as a longshot if not impossible. Even within the World Health Organization (WHO), many leaders viewed global eradication as “an impossible goal” (Henderson, 2011, p. D8), or perhaps a “wishful fantasy” (Foege, 2011, p. 53). Only by a narrow margin of two votes did the World Health Assembly vote in 1966 to create a special program for smallpox eradication, to which WHO would contribute $2.5 million per year. Fearing that it would fail, Marcelino Candau, WHO’s Director-General from 1953 to 1973, had opposed launching the program (Henderson, 2011). And India – a main focus of Brilliant’s and Foege’s memoirs – was viewed as exceptionally challenging, due to its mode of government, size, population density, poverty, and cultural complexity – a place where even the WHO’s optimistic program leaders “expect[ed] to see smallpox make its last stand” (D. A. Henderson, quoted in Brilliant, 2016, p. 143). “Smallpox in India was different… In India, it seemed, smallpox was inevitable” (Foege, 2011, pp. 83-84).

Personal Vocation

On the level of the individual, Brilliant’s (2016) and Foege’s (2011) memoirs narrate how religion provided personal motivation, leading each of them to a sense of calling. Foege, a minister’s son who grew up “in a series of parsonages” (2011, p. 12), describes a more conventional process of discernment, recounting inspiration from Albert Schweitzer, a Nobel Prize winning missionary doctor, and a series of mentors. Less conventionally, he records his longstanding early interest in pursuing public health work in medical missions, and being “disturbed… that church groups did so much medical work in developing countries,” perhaps as a “useful proselytizing tool,” “yet took so little responsibility for disease prevention… churches should be working because of what they believe, not because of what they are trying to get other people to believe” (pp. 28-29).

Brilliant’s path was arguably far more surprising. Whereas Foege was “motivated by a deep Christian faith,” Brilliant was “dragged” to India by his wife of three years, so that he could meet her spiritual teacher (guru; Brilliant, 2016, pp. 167, 299). A newly trained physician, Brilliant had little interest, viewing his personal “journey [as] about putting science and medicine to use in order to help ease suffering” (p. 107). Unexpectedly, however, Brilliant’s wife’s guru, who had a high reputation in India, and to whom Brilliant too eventually became devoted, one day for no apparent reason informed Brilliant that he would “work for the United Nations… you are going to go to villages and give vaccinations against smallpox” (p. 126). Possessing “no experience in public health” (p. 126), Brilliant was utterly baffled. He had “no experience in public health, no training past internship… no training in epidemiology [and] had never even seen a case of smallpox” (pp. 142-143).

Only because of his guru’s ongoing insistence – surely a form of religious motivation, although not stereotypic of career discernment – Brilliant “kept going back to WHO, more than a dozen times by taxi, bus, rickshaw, and train,” a journey each time of “a dozen hours if everything went right” (p. 140) – and was repeatedly told that “hiring you is quite impossible” (p. 138), based on his near complete lack of proper background, as well as Indian legal restrictions on who could be hired by WHO, not to mention the fact that he was “younger by at least a decade than any foreigner… ever hired” by the regional WHO office. Eventually hired as an administrative assistant in the smallpox program, Brilliant was only sent into the field to do vaccinations as a last resort when a key field worker suddenly fell ill.

Collective Motivation and Leadership

Brilliant (2016) also recounts how smallpox eradication in India reflected the pivotal role of religious leadership, but in unexpected ways. On the same day that Brilliant’s guru informed him that he would work for the United Nations, his guru also told him that “smallpox… will be unmulan, eradicated from the world. This is God’s gift to humanity because of the dedicated health workers. God will help lift this burden of this terrible disease from humanity” (Neemkaroli Baba, quoted in Brilliant, 2016, p. 126). Because of his reputation for infrequent but accurate public prophecy, Brilliant’s guru’s prediction proved catalytic for motivating skeptical Indian officials. As explained by Brilliant (2016, p. 231):

Most of the time, when I entered a new town I went straight to meet the civil surgeon or medical officer. The minute I started talking about smallpox, the Indian official’s eyes would glaze over and he would politely usher me out of the office. I attached a huge picture of Maharaji [my guru] to the windshield of my jeep, [something] I wasn’t supposed to do. But when these Indian doctors noticed his picture, they would ask, in that very Indian way, “Who is this guru, and who is he to you?” I would tell them the story of Maharaji’s prediction that God, through the hard work of dedicated health workers, would make smallpox disappear. They would then ask some variant of “Is that the same guru who [made various specific well-known accurate prophecies]…” After I confirmed that he was, the real work started; I was escorted back inside, where the local medical officer and I could have another cup of chai and an honest conversation, not about gurus and prophecies, but about early detection, early response, reporting, and vaccination.

Previous histories of Indian smallpox eradication have failed to recount such dynamics of religious motivation (e.g., Brilliant, 1985; Henderson, 1980; World Health Organization, 1980).[3] An initial emphasis on technical and managerial historiography may be understandable, but ongoing elision of spiritual/cultural dynamics seems inadvisable, for as Foege (2011, pp. 52-53) explained:

[I]n retrospect, the belief that it could be done seems like the most important factor in the global eradication effort. The technology and the infrastructure were necessary, but the planning and hard work required to use them to full effect rested on the faith that eradication was possible. We all know the adage that some things have to be seen to be believed. In fact, the opposite is often true: some things have to be believed to be seen.

The fact of smallpox was so ingrained in human experience that we had our work cut out for us to convince people that eradication was not a wishful fantasy. The shift from doubt to belief was not unlike a religious conversion; it involved not just facts, but emotion, too. A person suddenly transformed by the vision of what was possible could not be stopped…. Like a communicable disease, the belief in smallpox eradication was infectious, with an incubation period, various degrees of susceptibility, and an increasing rate of spread that finally infected many who came in its path. Once this condition was shared by a critical mass of people, no barrier was insurmountable.

It may be impossible to know if collective religious motivators such as described by Brilliant played a critical role in enabling smallpox eradication. But to wonder seems natural. Foege (2011, p. 192) writes that “In retrospect, achieving the eradication of smallpox might look inevitable. In fact, though, the chain of events included so many opportunities for failure that success was not a given — and we knew it. We had no guarantee of success and were humbled so often that humility became a daily emotion.” The possibility that religious endorsements could have tipped the balance hardly seems extraordinary when set in the context of millennia of interactions between religion and public health (Holman, 2015; Porter, 2005).

Better History

Presently, however our understanding the interplay of cultural, religious, and technical factors in eradication is handicapped by the strong muting or exclusion of religious motivations from most histories of smallpox eradication. Improved and rebalanced histories would better inform practice and help guide the much-needed mainstreaming of proper attention to religious factors in public health training (Oman, 2018). Moreover, as lamented by Foege (2011, p. xix),

We lose our histories far too fast. In the dozens of public health efforts in which I have been involved throughout my career, the histories have rarely been written soon enough. Within years, sometimes within months, people’s accounts begin to differ. Often the participants simply do not keep journals or record their notes…. participants at the 2006 reunion of the first smallpox workers… were invited to record oral histories. Many commented that they had forgotten details, and their accounts were incomplete. Based on this experience, the CDC decided to collect oral histories from the people involved in the 2010 H1N1 influenza phenomenon right away, in 2010. This is a wise practice, for much that might benefit future generations can be learned from eyewitness accounts of important events.

Of course, not all roles of religion in smallpox eradication in India or elsewhere were prima facie salubrious. For example, Foege (2011, p. 59) described a novel smallpox outbreak with cases mysteriously distributed throughout a Nigerian city, which turned out to come from a church group that had refused vaccination based on religious convictions. More dramatically, Brilliant (2016) describes how a tribal chief in a remote Indian village firmly resisted vaccination, explaining that “only God can decide who gets sickness and who does not. It is my duty to resist your interference with his will” (p. 333). But the chief was no stereotypical religious bigot from central casting. After he and his family were ambushed, physically restrained, and vaccinated by force, he collected his wits and then offered hospitality to those who moments earlier had assaulted him and his family. “We have done our duty. We can be proud of being firm in our faith… You say you act in accordance with your duty… It is over. God will decide. Now I find that you are guests in my house. It is my duty to feed guests” (p. 333). Brilliant noted that the chief “was so firm in his faith, yet there was not a trace of anger in his words,” commenting that “it felt to me like a post-graduate course in cultural relativity” (p. 333). There followed a discussion between the chief and Indian members of the vaccination team (e.g., “You live by God’s will. I, too, have surrendered to God’s will – that is what the word ‘Islam’ means… But what is God’s will?… Could we bring the needle if it were not God’s will?… It is God’s will, and my dharma is to protect your children from smallpox,” pp. 334-335). Soon after, the remaining villagers came forward to be vaccinated.

Additional anecdotes scattered throughout these memoirs show many other roles played by religion. For example, Brilliant reports eradication team interactions with priests at temples dedicated to Shitala, the Indian Goddess of smallpox. Whereas most of the eradication team’s physicians expected the priests to hide smallpox cases, Brilliant (2016, p. 189) “was pleasantly surprised by [the priests’] cheerful willingness to help the eradication effort.” Similarly, leaders of Jainism, a religion that teaches nonviolence to all living creatures, despite their concerns that animal lives were taken in creating the vaccine, were persuaded to back the eradication effort (see Brilliant, p. 344). And after Brilliant noticed the vaccination scars on the arms of the Dalai Lama, His Holiness explained that he had been vaccinated four times during the Tibetan smallpox epidemic of 1948 because “each of the four Buddhist sects wanted to make certain that their vaccine was used to protect me” (p.263).

The full spectrum of religious roles in smallpox eradication is clearly much wider than presented in most smallpox histories. Only by collecting and reflecting upon accounts of these manifold roles can we understand their full significance for future public health efforts. Yet one implication seems clear: Religion can be a powerful collaborative force for disseminating not simply recognition of the value of meritorious public health initiatives, but also an active belief in the ability of such efforts to succeed. In social science terms, religion can powerfully boost collective efficacy (Butel & Braun, 2019; Tower et al., 2021; see also Oman et al., 2012, p. 279, n. 1), in some cases by bringing to bear beliefs in “divine agency… as a guiding supportive partnership requiring one to exercise influence” (Bandura, 2003, p. 172; see also Pargament et al., 1988). Such belief in our collective capacities is indispensable for facing today’s most daunting public health challenges, such as global climate change and resurgent pandemics. Culturally and spiritually rich, balanced, and instructive histories of past victories can fortify us for such challenges. Between them, these two valuable memoirs by Brilliant and Foege not only outline technical aspects of smallpox eradication, but set before us helpful portraits of many diverse functions served by religion and spirituality, factors that need better recognition in public health as key partners in the challenging work ahead.

References

Bandura, A. (2003). On the psychosocial impact and mechanisms of spiritual modeling. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 13(3), 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327582IJPR1303_02

Brilliant, L. B. (1985). The management of smallpox eradication in India. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Brilliant, L. B. (2016). Sometimes brilliant : The impossible adventure of a spiritual seeker and visionary physician who helped conquer the worst disease in history. New York: HarperOne.

Butel, J., & Braun, K. L. (2019). The role of collective efficacy in reducing health disparities: A systematic review. Family & Community Health, 42(1), 8-19. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000206

Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Eldridge, B. M. (2009). Calling and vocation in career counseling: Recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(6), 625-632. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015547

Foege, W. H. (2011). House on fire: The fight to eradicate smallpox. Berkeley: University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520948891

Henderson, D. A. (1980). Smallpox eradication. Public Health Reports, 95(5), 422-426.

Henderson, D. A. (2011). The eradication of smallpox – an overview of the past, present, and future. Vaccine, 29, D7-D9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.080

Holman, S. R. (2015). Beholden: Religion, global health, and human rights. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199827763.001.0001

Idler, E., Levin, J., VanderWeele, T. J., & Khan, A. (2019). Partnerships between public health agencies and faith communities. American Journal of Public Health, 109(3), 346-347. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2018.304941

Kegler, M. C., Kiser, M., & Hall, S. M. (2007). Evaluation findings from the institute for public health and faith collaborations. Public Health Reports, 122(November-December), 793-802.

Oman, D. (Ed.). (2018). Why religion and spirituality matter for public health: Evidence, implications, and resources. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73966-3

Oman, D., & Syme, S. L. (2018). Weighing the evidence: What is revealed by 100+ meta-analyses and systematic reviews of religion/spirituality and health? In D. Oman (Ed.), Why religion and spirituality matter for public health: Evidence, implications, and resources (pp. 261-281). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73966-3_15

Oman, D., Thoresen, C. E., Park, C. L., Shaver, P. R., Hood, R. W., & Plante, T. G. (2012). Spiritual modeling self-efficacy. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 4(4), 278-297. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027941

Pargament, K. I., Kennell, J., Hathaway, W., Grevengoed, N., Newman, J., & Jones, W. (1988). Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 27(1), 90-104. https://doi.org/10.2307/1387404

Porter, D. (2005). Health, civilization and the state: A history of public health from ancient to modern times: Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203980576

Ram Dass (1979). Miracle of love: Stories about Neem Karoli Baba. New York: Dutton.

Tower, C., Van Nostrand, E., Misra, R., & Barnett, D. J. (2021). Building collective efficacy to support public health workforce development. Journal of public health management and practice, 27(1), 55-61. https://doi.org/10.1097/phh.0000000000000987

Whyle, E., & Olivier, J. (2017). Models of engagement between the state and the faith sector in sub-Saharan Africa – a systematic review. Development in Practice, 27(5), 684-697. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2017.1327030

World Health Organization (1980). The global eradication of smallpox: Final report of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication, Geneva, December 1979. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Apart from images obtained from Wikimedia Commons, this article is copyright © 2022 Doug Oman.

[1]^Doug Oman, Adjunct Professor, School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley (DougOman@Berkeley.edu).

[2]^Images were recombined from versions accessed in May 2022 through Wikimedia Commons for Brilliant (link, original author Cashinj, CC BY-SA 4.0 license) and Foege (link, original from CDC, in public domain).

[3]^Perhaps the only exception, first published in the 1970s, is a brief narration by Brilliant of key events involving his guru (Brilliant in Ram Dass, 1979, pp. 163-169).